Let’s Learn LLL! Part 1

introduction#

I’ve been wanting to write this for a LONG time (since about mid-2023 maybe), but I never got around to doing it. Somehow I’ve been super productive for the past few days though1, so I thought I might as well cross one more thing off of my to-do list.

I’m splitting this introduction into the two parts: the first part (which you are reading now) will cover the mathematical background on lattices, while the second part will cover the applications of lattices in cryptography CTF challenges.

Anyways, since this is meant to be an introduction to lattices geared towards CTFers, I will not be very rigorous. Sorry.

prerequisites#

I’m going to assume that you know at least the basics of linear algebra; if you aren’t, you can still read on, but you may not be able to fully comprehend everything.

lattices#

Definition: A lattice \(\mathcal{L}\) that is spanned by basis vectors \(\boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{b}_n \in \mathbb{R}^m \) is defined as

\[ \mathcal{L}\left(\boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{b}_n\right) = \left\{ \sum x_i \boldsymbol{b}_i \mid x_i \in \mathbb{Z} \right\} \]The number \(n\) is termed the dimension of the lattice. Generally we require that the basis vectors should be linearly independent, and thus \(n \le m\). Furthermore, if \(n = m\), we say that the lattice is full-rank.

In other words, a lattice is the linear combinations of the basis vectors with integer coefficients.

Because a lattice is defined by \(n\) vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^m\), we can also represent a lattice as a matrix in \(\mathbb{R}^{n \times m}\), with the basis vectors forming the rows of the matrix.2

\[ \mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}\right) = \left\{ \mathbf{B}^\intercal \boldsymbol{x} \mid \boldsymbol{x} \in \mathbb{Z}^n \right\} \]Here are some examples of lattices:

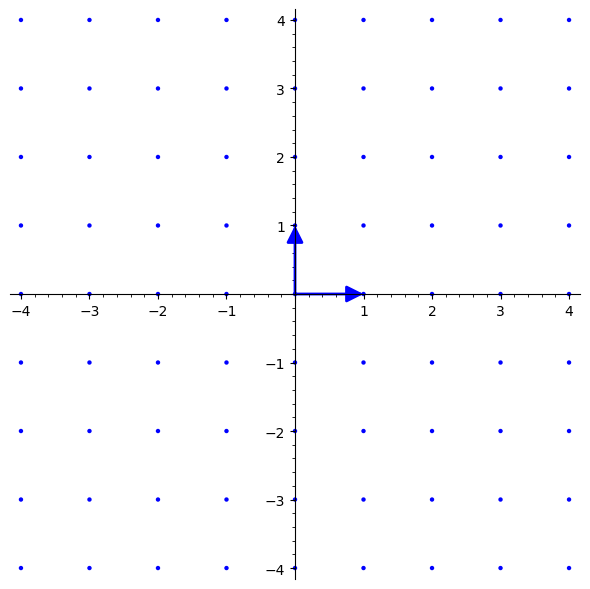

\[ \mathbf{B} = \begin{bmatrix}1 & 0\\0 & 1\end{bmatrix} \] \[

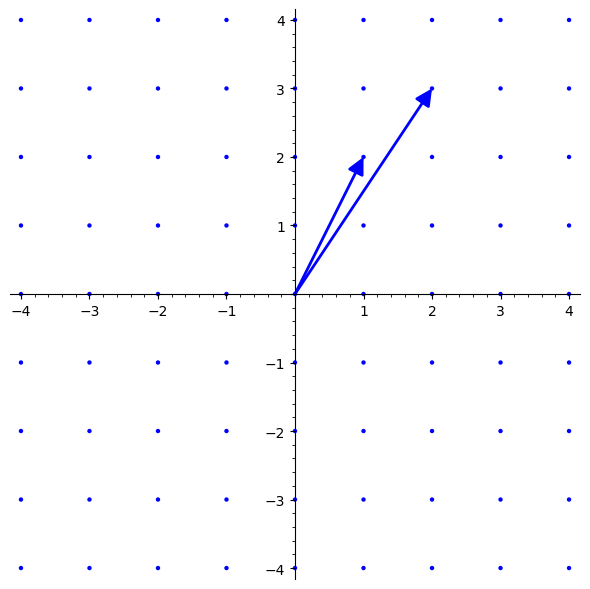

\mathbf{B} = \begin{bmatrix}2 & 3\\1 & 2\end{bmatrix}

\]

\[

\mathbf{B} = \begin{bmatrix}2 & 3\\1 & 2\end{bmatrix}

\]

You might have noticed that these two different bases span the same lattice. In fact, there are infinitely many bases that span the same lattice. The following theorem shows why:

Theorem: Two bases \(\mathbf{B}_1, \mathbf{B}_2 \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times m}\) span the same lattice if and only if there exists a unimodular matrix \(\mathbf{M} \in \mathbb{Z}^{n \times n}\) such that

\[ \mathbf{B}_1 = \mathbf{M} \mathbf{B}_2 \]

A unimodular matrix is a integer matrix that has determinant \(\pm 1\). An important property of unimodular matrices is that their inverses are also unimodular. By the way, unimodular matrices of \(\mathbb{Z}^{n \times n}\) form a group denoted as \(GL_n(\mathbb{Z})\).

Proof:

If: Since \(\mathbf{B}_1 = \mathbf{M} \mathbf{B}_2\), the rows of \(\mathbf{B}_1\) are integer linear combinations of the rows of \(\mathbf{B}_2\), and thus \(\mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}_1\right) \subseteq \mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}_2\right)\). Multiplying by \(\mathbf{M}^{-1}\) on both sides, we have \(\mathbf{M}^{-1} \mathbf{B}_1 = \mathbf{B}_2\), and \(\mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}_2\right) \subseteq \mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}_1\right)\) by a similar argument. Thus, we have that \(\mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}_1\right) = \mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}_2\right)\).

Only if: Since \(\mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}_1\right) = \mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}_2\right)\), the rows of \(\mathbf{B}_1\) are integer linear combinations of the rows of \(\mathbf{B}_2\) and vice versa. Thus, we have that \(\mathbf{B}_1 = \mathbf{M} \mathbf{B}_2\) and \(\mathbf{B}_2 = \mathbf{N} \mathbf{B}_1\) for integer matrices \(\mathbf{M}, \mathbf{N}\). From this we get \(\mathbf{B}_1 = \mathbf{M} \mathbf{N} \mathbf{B}_1\) and \( \left(\mathbf{I} - \mathbf{M} \mathbf{N} \right) \mathbf{B}_1 = \mathbf{0}\). Since we require the basis vectors of a lattice to be linearly independent, \(\mathbf{I} = \mathbf{M} \mathbf{N}\) and \(1 = \det\left(\mathbf{M} \mathbf{N}\right) = \det \mathbf{M} \det \mathbf{N}\). Since \(\mathbf{M}, \mathbf{N}\) are integer matrices, their determinants must be integers too. Thus, we have that \(\vert \det \mathbf{M} \vert = \vert \det \mathbf{N} \vert = 1\), and \(\mathbf{M}, \mathbf{N}\) are unimodular.

fundamental domains and blichfeldt’s theorem#

Definition: A fundamental domain of a lattice \(\mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}\right)\) is any region \(\mathcal{D}\left(\mathcal{L}\right)\) such that the following holds true:

\[ \bigcup_{x \in \mathcal{L}} \left(x + \mathcal{D}\right) = \text{span}\left(\mathbf{B}\right) \]

Informally, a fundamental domain is able to tile the span of the lattice basis by shifting by each lattice point. A specific fundamental domain of interest is the fundamental parallelepiped.

Definition: The fundamental parallelepiped of a lattice \(\mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}\right)\) with basis vectors \(\boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{b}_n\) is defined as

\[ \mathcal{P}\left(\mathcal{L}\right) = \left\{ \sum x_i \boldsymbol{b}_i \mid x_i \in \left[ 0, 1 \right) \right\} \]

In addition, we will also introduce the notion of the determinant for lattices.

Definition: The determinant of a lattice \(\mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}\right)\) with \(\mathbf{B} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times m}\) is defined as

\[ \det \mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}\right) = \sqrt{\det\left(\mathbf{B}\mathbf{B}^\intercal\right)} \]This quantity is also equal to the volume of the fundamental parallelepiped of \(\mathcal{L}\) treated as a \(n\)-dimensional simplex.

Now we are ready to prove Blichfeldt’s theorem, a theorem that can be thought of as a continuous version of the pigeonhole principle.

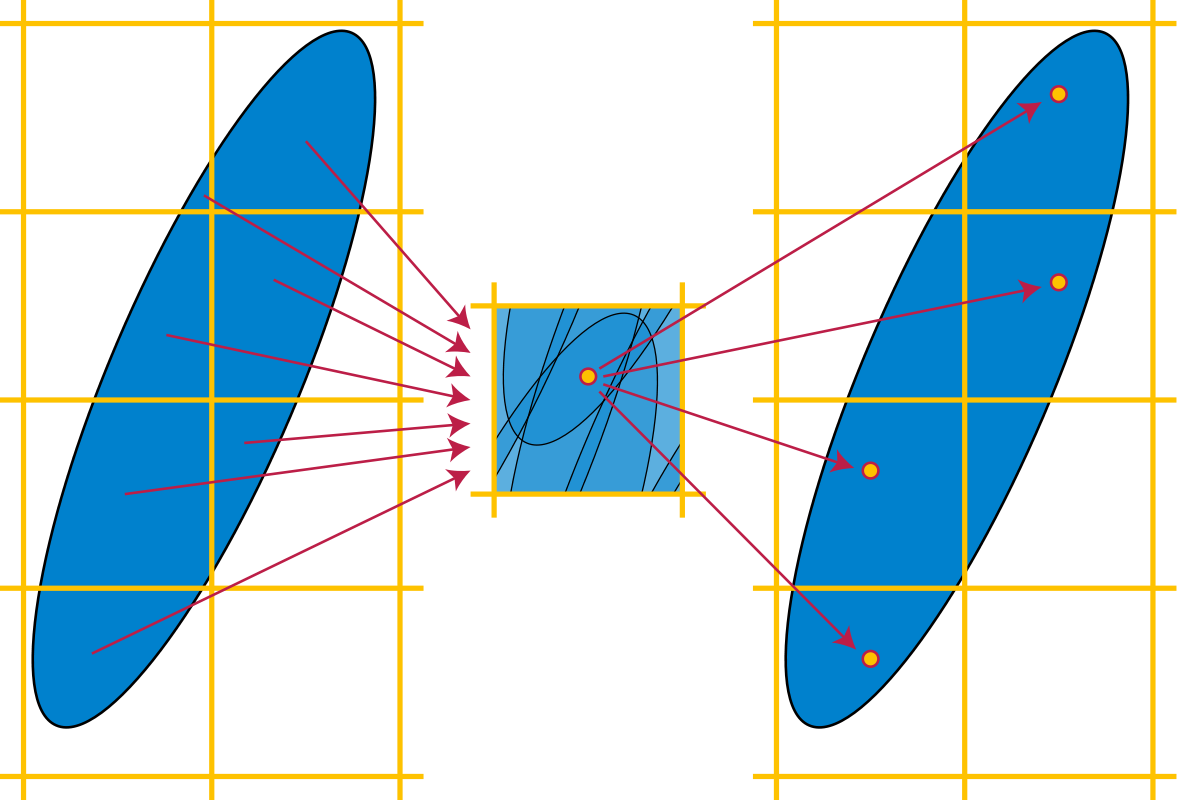

Theorem (Blichfeldt’s theorem): For a lattice \(\mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}\right)\), if a set \(S \subseteq \text{span}\left(\mathbf{B}\right)\) is such that \(\text{vol}\left(S\right) > \det \mathcal{L}\) then there exists \(x_1, x_2 \in S\) such that \(x_1 - x_2 \in \mathcal{L} \setminus \left\{0\right\}\).

A formal proof is left as an exercise to the reader3, but a basic idea of the proof is that if we cut up space into \(\mathcal{P}\left(\mathcal{L}\right)\) shaped chunks, since \(\text{vol}\left(S\right) > \det \mathcal{L}\), “by the pigeonhole principle” when we overlap all the chunks together there will always be multiple points in \(S\) overlapping one another.

Image from Wikipedia

An important corollary of this theorem is Minkowski’s theorem.

Theorem (Minkowski’s theorem): Let \(\mathcal{L}\) be an \(n\)-dimensional full-rank lattice. If a convex set \(S \subset \mathbb{R}^n\) is symmetric about the origin and \(\text{vol}\left(S\right) > 2^n \det \mathcal{L}\), then there exists a point \(x \in S \setminus \left\{0\right\}\) such that \(x \in \mathcal{L}\).

A convex subset means that \(\frac 12 \left(a+b\right) \in S\) for all \(a, b \in S\) and symmetric about the origin means that \(-x \in S\) for all \(x \in S\).

Proof: Let \(S\) be a set that satisfies the conditions, and let \(S' = \left\{x \mid 2x \in S\right\}\). Then \(\text{vol}\left(S'\right) = 2^{-n} \text{ vol}\left(S\right) \gt \det \mathcal{L} \) and by Blichfeldt’s theorem there exist \(x_1, x_2 \in S'\) such that \(x_1 - x_2 \in \mathcal{L} \setminus \left\{0\right\}\). From the definition of \(S'\) we have that \(2x_1, 2x_2 \in S\), so now consider \(\frac 12 \left(2x_1 - 2x_2\right)\). It is in \(S\) due to the conditions of convexity and symmetricity we imposed, and it is equal to \(x_1 - x_2 \in \mathcal{L} \setminus \left\{0\right\}\).

Minkowski’s theorem has an important application in bounding the length of the shortest vector, which we will discuss in greater length later.

tangent: fermat’s theorem (no, not that one)#

Let’s take a short break from all the theorems and definitions, and look at a rather interesting application of Minkowski’s theorem.

In 1640, Fermat wrote in a letter to Mersenne that every prime \(p \equiv 1 \pmod 4\) can be expressed as \(x^2 + y^2\) with \(x, y \in \mathbb{Z}\). This theorem is today an elementary theorem in number theory, and like a certain other theorem Fermat did not provide a proof of his statement.

Fortunately, Euler “after much effort” found a proof based on infinite descent almost a hundred years later in the 1740s. Many other proofs followed, including Dedekind’s proofs(!) using Gaussian integers, and an incredible “one-sentence proof” that you might have seen online before.

There is also a (in my opinion) very nice proof using lattices and Minkowski’s theorem, shown below.

Proof: From Euler’s Criterion, we know that \(-1\) is a quadratic residue modulo \(p\), as \(-1^{\frac{p-1}{2}} = 1\). Let \(i\) be an integer between \(0\) and \(p\) such that \(i^2 \equiv -1 \pmod p\). Now consider the lattice \(\mathcal{L}\) spanned by basis

\[ \mathbf{B} = \begin{bmatrix}1 & i\\0 & p\end{bmatrix} \]We can see that this \(\mathcal{L}\) is full rank and \(\det \mathcal{L} = p\). Consider the set \(S = \left\{\left(x, y\right) \mid x^2 + y^2 < 2p \right\}\), that is, a circle centered at the origin with radius \(\sqrt{2p}\). Minkowski’s theorem says that since \(\text{vol}\left(S\right) = 2 \pi p > 2^2 \det \mathcal{L}\), there exist nonzero integers \(m\) and \(n\) such that \(0 < m^2 + (mi + np)^2 < 2p\). Reducing the expression modulo \(p\), we have that

\[ \begin{align} m^2 + (mi + np)^2 &\equiv m^2 - m^2i^2 + 2mnip + n^2p^2\\ &\equiv m^2 - m^2\\ &\equiv 0 \end{align} \]and thus \(m^2 + (mi + np)^2 = p\).

Pretty cool. This proof is non-constructive (meaning that it does not explicitly state how to obtain the two numbers that when squared sum to \(p\)), but we’ll see in the next part how we can obtain a solution.

successive minimums#

Definition: the successive minimums for a lattice \(\mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}\right)\) with \(\mathbf{B} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times m}\) is \(\lambda_1, \lambda_2, \dots, \lambda_n\) defined as

\[ \lambda_i = \inf \left\{ \ell \mid i \le \dim\left(\text{span}\left(\mathcal{L}\,\cap\,\mathcal{B}_\ell\right)\right) \right\} \]where \(\mathcal{B}_\ell\) represents the sphere with radius \(\ell\), that is,

\[ \mathcal{B}_\ell = \left\{x \mid x \in \mathbb{R}^m, \Vert x \Vert \le \ell \right\} \]

What a mouthful. In simpler4 terms, the successive minimum \(\lambda_i\) is the length of the \(i\)th shortest vector in the lattice, discounting vectors that are a linear combination of the short vectors. However, note that just because the vectors corresponding to the successive minimums \(v_1, \dots, v_n\) are linearly independent, \(v_1, \dots, v_n\) does not form a basis for the same lattice. For example,

\[ \mathbf{B} = \begin{bmatrix}2\\&2\\&&2\\&&&2\\1&1&1&1&1\end{bmatrix} \]has successive minimum vectors

\[ \mathbf{\Lambda} = \begin{bmatrix}2\\&2\\&&2\\&&&2\\&&&&2\end{bmatrix} \]where the last row is obtained from \(2\boldsymbol{b}_5-\boldsymbol{b}_1-\boldsymbol{b}_2-\boldsymbol{b}_3-\boldsymbol{b}_4\). However, \(\mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{\Lambda}\right) \ne \mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{B}\right)\), as \(\boldsymbol{b}_5 \notin \mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{\Lambda}\right)\).

Remember how I mentioned Minkowski’s theorem can bound the length of the shortest vector? Here it is.

Theorem: For a full rank \(n\)-dimensional lattice \(\mathcal{L}\), the following holds:

\[ \lambda_1 \le \sqrt{n}\left(\det \mathcal{L}\right)^{1/n} \]

Note that \(\lambda_1\) is equal to the length of the shortest vector in \(\mathcal{L}\). The proof will again be left as an exercise to the reader, as it is quite a simple application of Minkowski’s theorem.

lattice basis reduction#

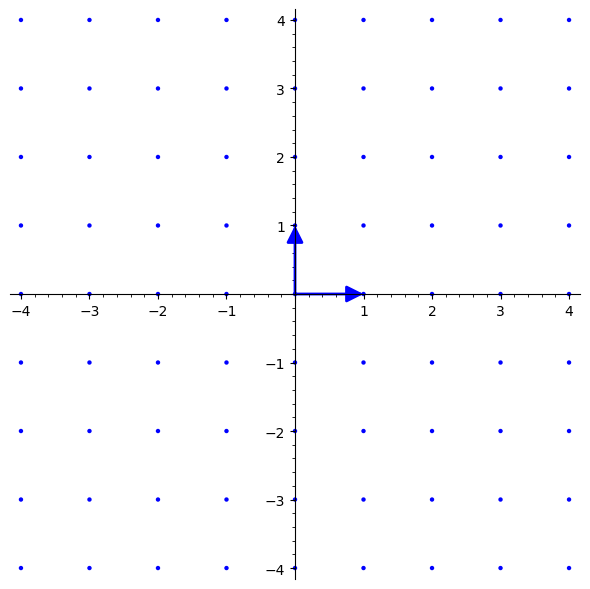

Earlier there was an example of two bases that span the same lattice; here they are again:

\[ \mathbf{B}_1 = \begin{bmatrix}1 & 0\\0 & 1\end{bmatrix} \] \[

\mathbf{B}_2 = \begin{bmatrix}2 & 3\\1 & 2\end{bmatrix}

\]

\[

\mathbf{B}_2 = \begin{bmatrix}2 & 3\\1 & 2\end{bmatrix}

\]

\(\mathbf{B}_1\) is, in a sense, a better basis for this lattice than \(\mathbf{B}_2\), because its basis vectors are shorter than \(\mathbf{B}_2\)’s. Lattice basis reduction is the process of transforming a lattice basis into a “better” one, where the basis vectors are hopefully shorter.

From here onwards, we will shift our attention from definitions to various lattice basis reduction algorithms, building up towards our final goal: the Lenstra-Lenstra-Lovász lattice basis reduction algorithm (LLL for short).

gram-schmidt orthogonalisation#

As a refresher, the Gram-Schmidt orthogonalisation algorithm takes in vectors \(\boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{b}_n\) and returns orthogonal vectors \(\boldsymbol{b}^\ast_1, \boldsymbol{b}^\ast_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{b}^\ast_n\) defined as

\[ \boldsymbol{b}^\ast_i = \boldsymbol{b}_i - \sum_{j=1}^{i-1} \mu_{i,j} \boldsymbol{b}^\ast_j \]where

\[ \mu_{i,j} = \frac{\langle\boldsymbol{b}_i, \boldsymbol{b}^\ast_j\rangle}{\langle\boldsymbol{b}^\ast_j, \boldsymbol{b}^\ast_j\rangle} \]For simplicity, I will be referring to \(\boldsymbol{b}^\ast\) and \(\mu\) as the Gram-Schmidt vectors and Gram-Schmidt coefficients respectively. Note that we are not normalising the vectors here.

Here are some properties of the Gram-Schmidt vectors that are important: for \(\boldsymbol{b}_1, \dots, \boldsymbol{b}_n \in \mathbb{R}^m\) forming the basis of lattice \(\mathcal{L}\),

- \(\Vert \boldsymbol{b}^\ast_i \Vert \le \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_i \Vert\)

- \(\langle\boldsymbol{b}_i, \boldsymbol{b}^\ast_i\rangle = \langle\boldsymbol{b}^\ast_i, \boldsymbol{b}^\ast_i\rangle\)

- \(\det \mathcal{L} = \prod_{i=1}^{n} \boldsymbol{b}^\ast_i\)

Now, using the Gram-Schmidt vectors as a basis (get it), we can define the orthogonality defect of a basis to be

\[ \delta = \frac{\prod^n_{i=1} \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_i\Vert}{\det \mathcal{L}} \]Since the determinant of the lattice is equal to the product of the Gram-Schmidt vectors, the orthogonality defect is essentially a measure of how not orthogonal a basis is. In the case where a basis is already orthogonal, the orthogonality defect is 1. It’s also easy to see that for all bases, \(\delta \ge 1\).

Unfortunately, the Gram-Schmidt vectors are not always a basis of the lattice spanned by the original vectors. Let’s now look at actual lattice basis reduction algorithms, starting with a simple one for 2D lattices.

lagrange’s algorithm#

Lagrange first formulated the notion of a reduced basis for a 2D lattice while researching quadratic forms in an article published in 1773.

Definition: A basis \(\left(\boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2\right) \in \mathbb{R}^{2 \times m}\) is said to be Lagrange-reduced (or simply reduced) if and only if \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert \le \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert\) and \(\vert\langle \boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2 \rangle\vert \le \frac{1}{2}\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2\).

This definition is actually equivalent to the (perhaps simpler) definition with the condition that \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert \le \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert \le \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2 + k\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert\) for all integer \(k\).

Proof: Consider \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2 + k\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2\). We have that for all integer \(k\),

\[ \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2 + k\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2 = \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert^2 + k^2 \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2 + 2k\langle\boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2\rangle \]Since \(\vert\langle \boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2 \rangle\vert \le \frac{1}{2}\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2\), it follows that \(-k\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2 \le 2k\langle\boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2\rangle \le k\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2\) and thus \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2 + k\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2\) is bounded from below as follows:

\[ \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert^2 + k^2 \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2 - \vert k \vert \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2 \le \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2 + k\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2 \]As \(k^2 \ge \vert k \vert\), we have that \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert^2 \le \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2 + k\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2\) and the desired result is obtained upon taking square roots on both sides.

For the converse, we square, subtract \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert^2\), then divide by \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2\) on both sides of the inequality \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert \le \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2 + k\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert\) to get

\[ 0 \le 2k\frac{\langle\boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2\rangle}{\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert} + k^2 \]for all integer \(k\). By considering the cases where \(k=1\) and \(k=-1\), we can see that \(-\frac{1}{2} \le \frac{\langle\boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2\rangle}{\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert} \le \frac{1}{2}\), and the desired result follows.

In fact, another equivalent definition is \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert \le \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert \le \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1 \pm \boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert\). As usual, the proof will be left as an exercise.

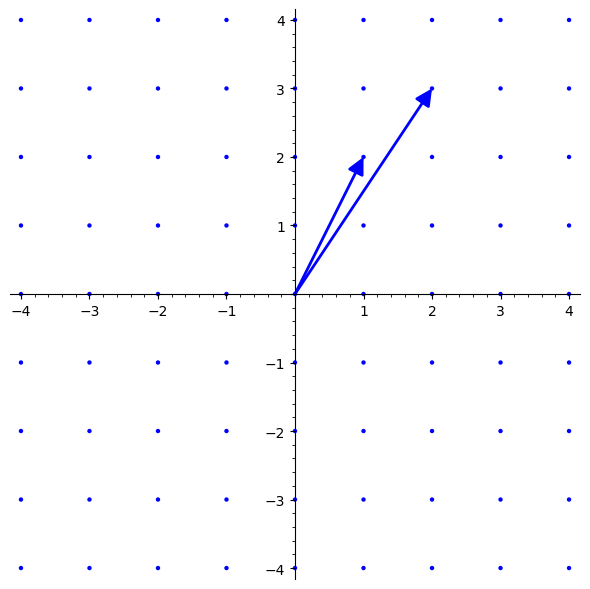

Geometrically, the Lagrange reduction constraints mean that \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert\) must be shorter than \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert\), and the angle between them must be smaller than \(\frac{\pi}{3}\) or greater than \(\frac{2\pi}{3}\). The longer \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert\) is compared to \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert\), the less orthogonal they must be.

Now, we will prove that \(\boldsymbol{b}_1\) and \(\boldsymbol{b}_2\) satisfying these conditions are indeed reduced.

Theorem: For \(\boldsymbol{b}_1\) and \(\boldsymbol{b}_2\) satisfying the Lagrange reduction constraints, they are the shortest vectors in the lattice spanned by them. That is, \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert = \lambda_1\) and \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert = \lambda_2\).

Proof: We will first prove that \(\boldsymbol{b}_1\) is indeed a shortest vector, then prove that \(\boldsymbol{b}_2\) is a next shortest vector that forms a basis together with \(\boldsymbol{b}_1\).

For an arbitrary nonzero vector in the lattice \(\boldsymbol{v} = k_1\boldsymbol{b}_1 + k_2\boldsymbol{b}_2\) with \(k_1, k_2 \in \mathbb{Z}\) not both zero. Consider \(\Vert\boldsymbol{v}\Vert\).

\[ \begin{align} \Vert\boldsymbol{v}\Vert^2 &= k_1^2 \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_1 \Vert^2 + k_2^2 \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_2 \Vert^2 + 2 k_1 k_2 \langle \boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2 \rangle\\ &\ge k_1^2 \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_1 \Vert^2 + k_2^2 \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_1 \Vert^2 + 2 k_1 k_2 \langle \boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2 \rangle &&\because \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert \le \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert\\ &\ge k_1^2 \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_1 \Vert^2 + k_2^2 \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_1 \Vert^2 - \vert k_1 k_2 \vert \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_1 \Vert^2 &&\because 2\vert k_1k_2\langle\boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2\rangle\vert \le \vert k_1k_2 \vert \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2\\ &= \left(k_1^2 + k_2^2 - \vert k_1k_2 \vert\right)\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2\\ &\ge \left(\vert k_1 \vert - \vert k_2 \vert\right)^2 \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2\\ \end{align} \]Note that we only need to consider the case where \(k_1, k_2 > 0\). Completing the square,

\[ \begin{align} \Vert\boldsymbol{v}\Vert^2 &\ge \left(\left(k_1 - \frac{k_2}{2}\right)^2 + \frac{3}{4}k_2^2\right) \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2\\ &\ge \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert^2 &&\because k_1, k_2 \ne 0 \end{align} \]Thus, \(\Vert\boldsymbol{v}\Vert \ge \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert\) for all vectors in the lattice, and so \(\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert = \lambda_1\).

Now, let \(\boldsymbol{v} = k_1\boldsymbol{b}_1 + k_2\boldsymbol{b}_2\) with \(k_1, k_2 \in \mathbb{Z}\) not both zero be a vector that, together with \(\boldsymbol{b}_1\), forms a basis for the lattice. Clearly \(k_2 \ne 0\). Let \(q, r\) be integers such that \(k_1 = qk_2 - r\) and \(0 \le r < k_2\). We have that

\[ \begin{align} \boldsymbol{v} &= \left(qk_2 - r\right)\boldsymbol{b}_1 + k_2\boldsymbol{b}_2\\ &= k_2\left(q\boldsymbol{b}_1 + \boldsymbol{b}_2\right) - r\boldsymbol{b}_1\\ \end{align} \]Now, by the reverse triangle inequality,

\[ \begin{align} \Vert\boldsymbol{v}\Vert &\ge \vert k_2\Vert q\boldsymbol{b}_1 + \boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert - r\Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert\vert\\ &\ge \vert \left(k_2-r\right)\Vert q\boldsymbol{b}_1 + \boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert\vert &&\because \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert \le \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_2 + k\boldsymbol{b}_1\Vert \space \forall k \in \mathbb{Z}\\ &\ge \Vert q\boldsymbol{b}_1 + \boldsymbol{b}_2\Vert &&\because r < k_2\\ &\ge \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_2 \Vert \end{align} \]

Lagrange’s algorithm can be thought of as a 2D version of a variant of the Euclidean algorithm for finding the greatest common divisor of two numbers. Pseudocode (Python flavoured) for both algorithms are presented below:

# centered euclidean algorithm

def euclid(x, y):

if abs(x) <= abs(y):

x, y = y, x

while y != 0:

k = round(x/y)

x, y = y, x - k*y

return abs(n)

# lagrange's algorithm

def lagrange(x, y):

if x.norm() < y.norm():

x, y = y, x

while x.norm() > y.norm():

k = round((x*y)/y.norm()^2)

x, y = y, x - k*y

return x, y

Just for simplicity of proof later, we will assume that round() or \(\lceil \cdot \rfloor\) rounds halves towards zero; that is, \(\lceil 1.5 \rfloor = 1\) and \(\lceil -1.5 \rfloor = -1\). While the termination conditions for both algorithms differ, we can notice that both algorithms first ensure that the first parameter is larger than the second, and perform a “reduction” operation based on the rounded value of the “quotient” of both parameters.

To finish off this section, we will prove that Lagrange’s algorithm does indeed return a basis satisfying the Lagrange reduction conditions.

Proof: It is evident that \(\left(\boldsymbol{y}, \boldsymbol{x} - k\boldsymbol{y}\right)\) in the loop spans the same lattice as \(\left(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\right)\). It is evident that Lagrange’s algorithm terminates; if the while loop were to not terminate, an infinite series of vectors in the lattice with strictly decreasing norm would exist, but we know that there is a smallest vector for every lattice.

Now we prove that the algorithm returns a reduced basis when it terminates. Call the vectors used in the last iteration of the loop \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and \(\boldsymbol{y}\). We need to prove that \(\Vert y\Vert \le \Vert\boldsymbol{x} - k\boldsymbol{y}\Vert\) and \(\vert\langle \boldsymbol{y}, \boldsymbol{x} - k\boldsymbol{y} \rangle\vert \le \frac12 \Vert y\Vert^2\). The former is trivial by the termination of the algorithm, the latter can be proved by observing that

\[ \begin{align} \vert\langle \boldsymbol{y}, \boldsymbol{x} - k\boldsymbol{y} \rangle\vert &= \vert\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y} \rangle - k \Vert\boldsymbol{y}\Vert^2 \vert\\ &= \vert \mu \Vert\boldsymbol{y}\Vert^2 - k \Vert\boldsymbol{y}\Vert^2 \vert\\ &= \vert \mu - k \vert \Vert\boldsymbol{y}\Vert^2\\ &\le \frac12 \Vert\boldsymbol{y}\Vert^2 &\because k = \lceil \mu \rfloor \end{align} \]

the lenstra-lenstra-lovász (LLL) algorithm#

Lagrange’s algorithm, while guaranteed to return the most reduced basis in a lattice, only works for 2 dimensional lattices. The LLL algorithm, on the other hand, works for all lattices, but is not guaranteed to return the “most” reduced basis. We first need to define a new criteria for reducedness for a general lattice, since Lagrange reduction does not work well beyond 2 dimensions.

Definition: A basis \(\left(\boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{b}_n\right)\) is said to be \(\delta\)-LLL-reduced if and only if the following two conditions hold.

- For all \(1 \le j < i \le n\), \(\left\vert\mu_{i, j}\right\vert \le \frac12\) (size reduction)

- For all \(1 \le i < n\), \(\left(\delta - \mu^2_{i+1, i}\right)\left\Vert\boldsymbol{b}^\ast_{i}\right\Vert^2 \le \left\Vert\boldsymbol{b}^\ast_{i+1}\right\Vert^2\) (Lovász condition)

where \(\boldsymbol{b}^\ast\) and \(\mu\) are the Gram-Schmidt vectors and coefficients as mentioned previously, and \(\frac14 < \delta < 1\).

The first condition can also be seen in the definition of Lagrange reduction, but the second is new and might be confusing at first glance. Unfortunately, I’ve not quite gained complete understanding of how these two conditions aid reduction and the algorithm itself, so I will link to a good overview of LLL by Cryptohack.5 The algorithm itself can be roughly described as repeatedly performing Gram-Schmidt orthogonalisation (rounding the \(\mu\)s to ensure that the new vectors are still in the lattice) and swapping pairs of vectors by a heuristic represented by the Lovász condition.

We will be proving a claim about a bound on the length of the shortest vector in the basis returned by LLL.

Claim: for a LLL-reduced basis \(\left(\boldsymbol{b}_1, \boldsymbol{b}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{b}_n\right)\) of the lattice \(\mathcal{L}\), the shortest vector \(\boldsymbol{b}_1\) satisfies

\[ \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_1 \Vert \le \left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{(1-n)/4} \left( \det \mathcal{L} \right)^{1/n} \]Proof: By using the LLL-reduction conditions, we have that

\[ \begin{align} \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_i \Vert^2 &= \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_i^\ast \Vert^2 + \sum_{j=1}^{i-1} \mu_{i,j}^2 \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_j^\ast\Vert^2\\ &\le \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_i^\ast \Vert^2 + \frac{1}{4} \sum_{j=1}^{i-1} \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_j^\ast\Vert^2 &&\text{(from size reduction)}\\ &\le \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_i^\ast \Vert^2 + \frac{1}{4} \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_i^\ast\Vert^2 \sum_{j=1}^{i-1} \prod_{k=j}^{i-1} \left(\delta - \mu^2_{k+1,k}\right)^{-1} &&\text{(from Lovász condition)}\\ &\le \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_i^\ast \Vert^2 + \frac{1}{4} \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_i^\ast\Vert^2 \sum_{j=1}^{i-1} \prod_{k=j}^{i-1} \left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{-1} &&\text{(from size reduction)}\\ &= \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_i^\ast \Vert^2 + \frac{1}{4} \Vert\boldsymbol{b}_i^\ast\Vert^2 \sum_{j=1}^{i-1} \left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{j-i}\\ &= \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_i^\ast \Vert^2 \left( 1 + \frac{1}{4} \frac{\left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{-i} - \left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{-1}}{\left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{-1} - 1}\right)\\ \end{align} \]Now note that the mess in the brackets is \(\le \left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{1-i}\) for \(i \ge 1\), so furthermore we have that

\[ \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_i \Vert^2 \le \left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{1-i} \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_i^\ast \Vert^2 \]By again using the two conditions, we have that for \(i \le j\),

\[ \begin{align} \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_i \Vert^2 &\le \left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{1-i} \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_i^\ast \Vert^2\\ &\le \left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{1-i} \left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{i-j} \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_j^\ast \Vert^2\\ &= \left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{1-j} \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_j^\ast \Vert^2 \end{align} \]and in particular, for \(1 \le i\), \(\Vert \boldsymbol{b}_1 \Vert \le \left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{(1-i)/2} \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_i^\ast \Vert\). Now,

\[ \begin{align} \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_1 \Vert^n &\le \prod_{i=1}^n \left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{(1-i)/2} \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_i^\ast \Vert\\ &= \left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{n(1-n)/4} \det \left( \mathcal{L} \right) \end{align} \]so we have, as desired,

\[ \begin{align} \Vert \boldsymbol{b}_1 \Vert \le \left(\delta - 1/4\right)^{(1-n)/4} \left( \det \mathcal{L} \right)^{1/n} \end{align} \]

This bound is different from the Minkowski’s bound mentioned earlier; Minkowski’s bound is algorithm agnostic and applies for every single basis, while this bound is specific for LLL-reduced bases. Funnily enough, for lattices with small dimension, this bound actually outperforms Minkowski’s bound if \(\delta\) is chosen correctly.

Generally, the larger the value of \(\delta\) is, the “better” your reduced basis will be, but if \(\delta > 1\) the algorithm is not guaranteed to run in polynomial time (i.e. fast enough). By default, Sage uses \(\delta = 0.99\), but in certain cases smaller values like \(0.75\) would also work.

conclusion#

There are a lot of other lattice reduction algorithms out there (BKZ, flatter) that have their own advantages and disadvantages, but LLL is probably the most well-known. If you’re interested about lattices, you should definitely read up more about them!

Sorry if it seems like there’s not a lot of content about LLL in this post, but I couldn’t really write about the actual algorithm itself in a satisfactory way, and it ended up draining a lot of my time and energy, so I resorted to linking to other people’s work.6 I hope you still learnt something from this post though!

Stay tuned for the next part where we actually use LLL to do crypto challenges!

burn out recovery real? probably not. we’ll see (edit: it was not real) ↩︎

in other resources about lattices you might see basis vectors arranged as columns but i am using rows because that’s how sage does it ↩︎

read: i’m too lazy to write the proof here :3 ↩︎

less mathy, that is ↩︎

this feels like cheating but honestly ive been trying to write and explain it for the better part of about a year and still nothing feels correct so maybe this is for the better ↩︎

in fact the one section on LLL took about 5 times longer to write than the rest. this entire post took ONE YEAR and a couple of days to write, so some parts/notation might feel inconsistent. can you tell? ↩︎