BlahajCTF 2025 Author Writeups & Commentary

Introduction#

This year was the 3rd iteration of BlahajCTF, organised by a bunch of friends and I. We scaled up our event quite considerably as compared to last year, with about twice the amount people attending the physical finale/final round of the CTF. It wasn’t entirely smooth sailing, but I really enjoyed working with the rest of the organisers and I’m glad that I had this chance to work with such talented and wonderful people.

Writeups#

I wrote five challenges this year; four crypto and one misc. I’ll be giving detailed(?) writeups for them, as well as some commentary. You can find the challenge sources and solve scripts in the official challenge repository (probably releasing soon).

Unfortunately, both of my challenges in qualifiers (crypto/cats and crypto/rot13) had unintended solutions (in fact crypto/cats was cheesed so hard that it got blooded within 9 minutes). I patched the unintended solution for crypto/cats and re-released it in finals as crypto/cats-revenge, but crypto/rot13 wasn’t patched because that would have tilted the category proportion of finals a bit too much. crypto/liar-dancer in finals also had an unintended solution.

Furthermore, it was a bit sad to see that most of my challenges could be oneshotted using codex, but I suppose that is inevitable for challenges in a beginner oriented CTF. I sincerely hope that people who completely relied on ChatGPT and codex to solve my challenges can learn something from this post.

crypto/liar-dancer, 34 solves#

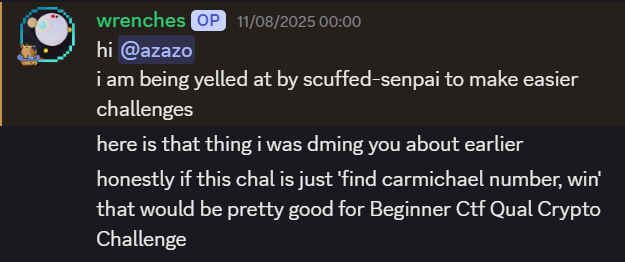

My good friend wrenches brought up the idea of using carmichael numbers in a challenge.

But of course, if the challenge were just “find carmichael number, win” it would not be very interesting. Eventually we settled upon relying on the fact that Carmichael numbers can fool the Fermat primality test: from Fermat’s little theorem, we know that \(a^{p-1} \equiv 1 \bmod p\) for all \(a\) not a multiple of \(p\). Therefore, for a number \(n\), we can repeatedly choose random \(a\) between \(2\) and \(n-2\) and see if \(a^{n-1} \equiv 1 \bmod n\). If the equivalence is false, we know that \(n\) is composite for sure.

However, Carmichael numbers are quite literally defined to be exceptions to the Fermat primality test: a Carmichael number is a composite number \(n\) such that \(a^{n-1} \equiv 1 \bmod n\) for all \(a\) coprime to \(n\). Since we are checking the congruence for a lot of random values, we can guess that the intended solution is to probably submit Carmichael numbers instead of praying that a random composite number passes the primality check.

If you dig around for long enough, you eventually find the following way of constructing Carmichael numbers: if \(6k+1\), \(12k+1\) and \(18k+1\) are all prime (which is conjectured to happen infinitely times), then \(n = (6k+1)(12k+1)(18k+1)\) is a Carmichael number. This can be proven by considering Korselt’s criterion.

We also want our Carmichael number minus one to be unsmooth: \(n-1 = 36k(36k^2 + 11k + 1)\) needs to have a prime factor larger than \(2^{100}\). This is not that hard to do; in my solve script I just asserted for \(36k^2 + 11k + 1\) to be a prime.

So we have a Carmichael number that passes all the checks. Hooray! Now we just need to solve the DLP modulo it. The order of the group we’re working with is \(\phi(n) = 1296k^3\) with \(k\) less than 60 bits, which is incredibly smooth, so we should have no problem solving the DLP.

One final issue is that since \(\lambda(n) = 36k\), we can only recover the value of the flag modulo a small number, but we can just repeatedly connect to the server and submit different Carmichael numbers generated the same way, then CRT the values together to recover the full flag. There was a participant who was stuck on this step (I think) during the last hour of the CTF or so which was kind of sad, and I couldn’t give any hints because by then a lot of people had solved the challenge.

Unfortunately, this challenge had an unintended solution where one could just submit a normal safe prime, then solve the DLP modulo smaller prime factors of the order. Since you can essentially query the server an unlimited amount of times, you can just get a lot of congruences with small prime factors and CRT them together instead.

crypto/polyRSA, 43 solves#

Honestly, there’s not much to say for this challenge; this challenge wasn’t meant to be too hard. I was inspired by challenges from GreyCTF 2023 that do traditional crypto setups in nontraditional structures1:

- DLP with matrices

- DLP in a quotient group of \(\mathbb{F}_p[x, y]\)

- RSA in a quadratic field So I decided to do RSA in a polynomial ring.

The challenge first turns the flag into a polynomial \(m(x)\) in \(\mathbb{F}_{p}[x]\) with \(p = \text{next_prime}(2^{32})\), with each coefficient representing four characters. Then, two “prime” polynomials (with prime coefficients) are generated in the same ring, and multiplied to form the modulus \(N(x)\). The flag is then encrypted as with normal RSA, resulting in the ciphertext \(c(x) = m(x)^{65537} \bmod{N(x)}\).

The security of RSA relies on the difficulty of factoring the modulus, by nature of it being the product of two large primes. However, in this case, the modulus is easily factorisable, and as such we can decompose the quotient ring with CRT: for \(N(x) = f_1^{e_1}(x)f_2^{e_2}(x) \dots f_n^{e_n}(x)\),

\[ \mathbb{F}_{p}[x]/N(x) \cong \mathbb{F}_{p}[x]/f_1^{e_1}(x) \times \mathbb{F}_{p}[x]/f_2^{e_2}(x) \times \dots \mathbb{F}_{p}[x]/f_n^{e_n}(x) \]So the order of \(\mathbb{F}_{p}[x]/N(x)\) is \(\text{lcm}( (p^{d_1} - 1)^{e_1}, (p^{d_2} - 1)^{e_2}, \dots, (p^{d_n} - 1)^{e_n} )\), where \(d_i\) is the degree of \(f_i\). With the order, we can then invert \(65537\) modulo it and decrypt the ciphertext.

There is one last little problem: the flag is encoded into a degree 16 polynomial, but the modulus also has degree 16, so polynomial we get after decrypting the ciphertext isn’t the actual flag. We need to add back a multiple of the modulus by leveraging the fact that the leading coefficient will be b"blah" to finally recover the correct flag.

crypto/rot13, 11 solves#

I don’t think I’ve ever seen a local CTF do something with oblivious transfer, so I made this challenge. It’s a normal RSA setup, except one of the primes is split equally into MSB, LSB, and middle, and you can choose to receive one of the three through oblivious transfer.

The solution uses a trick that I first saw in idekCTF that gets the sum of two options, but its not that hard to derive from first principles. If, instead of submitting \(v = x_i + k^e\) like the challenge expects, one submits \(v = (x_0 + x_1)/2\), they can recover the sum of \(m_0\) and \(m_1\) since

\[ \begin{align} c_0 + c_1 &= m_0 + m_1 + k_0 + k_1\\ &= m_0 + m_1 + (v - x_0)^d + (v - x_1)^d\\ &= m_0 + m_1 + \left(\frac{x_1 - x_0}{2}\right)^d + \left(\frac{x_0 - x_1}{2}\right)^d\\ &= m_0 + m_1 \end{align} \]With two thirds of the bits of the prime known, one can then just use Coppersmith’s method to recover the entire prime, then trivially decrypt the ciphertext to get the flag. Initially I wanted to shift everything right so there are no trailing 0s in the hints for the prime, but I don’t think this is solvable, and also we had enough hard challenges for a beginner oriented CTF.

Quite unfortunately, since I did not bother generating a different set of keys for the oblivious transfer and just used the same modulus as the one used for encrypting the flag, the OT setup basically turns into a semi-decryption oracle.

crypto/cats, 66 solves; crypto/cats-revenge, 13 solves#

This challenge was inspired by those clickbaity math puzzle/memes with fruits for variables. I like them a lot, especially when they seem to be very simple but are actually hard. the last one, in particular, is a classic. I first saw it about 6 years ago, back when I still did not know what an elliptic curve was.

After I started doing cryptography challenges in CTFs and learnt what an elliptic curve is, I also rediscovered its applications in solving diophantine equations like this. I had the idea of turning it into a CTF challenge around the end of 2023. Originally this challenge was supposed to be used in BlahajCTF 2024 but it did not really work out well, so I modified it a bit and here it is in 2025.

This also was not meant to be a particularly difficult challenge if you are familiar with the more mathematical theory behind elliptic curves. Sage easily lets you turn the plane cubic into an elliptic curve with corresponding elliptic curve, and also gives you the corresponding morphisms between the two. Then, we can just get a generator of the curve and find a large multiple of it that, when turned back into a solution for the cubic, passes the size check.

You might notice that in the source code, there is a strange array from secret import vals that the right hand side value in the equation is chosen from. This is because for some values, the corresponding elliptic curve actually has rank zero, so there are no solutions to the equation. After some research I found a sufficient (but not necessary) condition for the curve to have nonzero rank by considering the root number: let the number on the right hand side of the equation be \(s\). Then, consider the number of factors of \(s^3 - 27\) not including multiplicity that are equivalent to \(1 \bmod 3\). If, furthermore, \(3 \vert s\) and \(s \not\equiv 12 \pmod{27}\), add one to the number. The rank will be odd (and thus nonzero) if the final number is even. Perhaps if there is enough time in the future, I will write a separate post about this.

misc/pale-horses, 4 solves#

My self-set quota for BlahajCTF was at least 5 challenges. This is the fifth. I was inspired by this tweet and originally wanted to make something similar, but it would be too derivative and not novel/interesting enough. Then, I thought of using Python bytecode instead of x86. This makes working with words only kind of impossible, because it’s Really Really Hard to work with completely alphabetical bytecode in Python (especially in newer versions). So instead of needing to be English words, I decided to change the plot of the challenge to the bytecode needing to be valid Python code as well. I asked wrenches for help (because she had a similar challenge idea that is unfortunately scrapped) and eventually we settled on this version…

#!/usr/bin/python3.13

def recompile(bytecode):

co = compile('()', '<string>', 'eval')

code = co.replace(co_code=bytecode, co_consts=())

return code

s = bytes.fromhex(input("> "))

assert eval(recompile(s)) == eval(s)

print("blahaj{REDACTED}")

…at least, until during the qualifiers round, when the sheer number of people solving challenges using AI made us want to buff this challenge. However, we couldn’t really make it harder while maintaining its aesthetics/elegance, and in the end we came up with two extra checks:

#!/usr/bin/python3.13

def recompile(bytecode):

co = compile('()', '<string>', 'eval')

code = co.replace(co_code=bytecode, co_consts=())

return code

def safe_eval(s):

return eval(s, {"__builtins__": {}})

try:

s = bytes.fromhex(input("> "))

assert s.decode().isprintable()

assert safe_eval(recompile(s)) == safe_eval(s)

print("blahaj{REDACTED}")

except Exception:

exit(0)

These extra checks were mainly cosmetical and didn’t really make the challenge that difficult, but this challenge still only got 4 solves, which is quite surprising. Shoutout to the one person that did this challenge by hand :)

Anyways, pre-buff there’s basically two ways to go about this challenge: either you make the Python code “return early” and ignore additional bytes with #, or you make the bytecode return early and make the Python code ignore the bytecode payload somehow. My first payload went with the first method and was

payload = b"OSError.mro().__len__()-4"

payload += b'#'*(166-len(payload)) + b' \x01\x19\x01\x19\x01L\x05*\x01)\x01$\x02'

which, when evaluated as Python code, just returns 0. When executed as bytecode, it first executes the instruction corresponding to O (which is JUMP_FORWARD) with argument S or 83. Then, we pad the payload with random instructions, and at instruction number 83 we have

0 POP_TOP

1 LOAD_LOCALS

LOAD_LOCALS

IS_OP 5

UNARY_NEGATIVE

UNARY_INVERT

RETURN_VALUE

which is just a way to get the number 0. When I sent the challenge to wrenches for her to test it, her payload was

224f4f222c7072696e742e5f5f73656c665f5f2e627265616b706f696e742829231e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e1e19012401

or

"OO",print.__self__.breakpoint()#\x1e\x1e...\x1e\x1e\x19\x01$\x01

which, similarly, puts the Python payload at the front and ignores most of the bytecode with #. However, her bytecode returns locals(), and instead calls the breakpoint() method in Python. I did not like this very much, because I didn’t want the challenge to become just another pyjail, but at that time I did not really give the matter much thought.

After imposing stricter conditions (no nonprintable characters, no __builtins__), we are somewhat forced to return early from the bytecode instead, because it’s hard to write valid bytecode with printable characters only. A solution was

".#".__class__.__class__("",(),{"__eq__":lambda s,o:True})()

which returns early from bytecode with #, corresponding to the RETURN_GENERATOR instruction. Everything after the return is ignored by the interpreter as long as the bytecode has an even length. In the Python section, we create a new object that has its __eq__ overloaded to return True for every comparison using the type() function (this is a new way of using type() that I did not know about before). The __class__ nonsense is just a way to get type() without __builtins__.

Another cool solution a participant shared with me was

U"+ + $ "[0:0]==""

which, for the bytecode section, does something like

0 LOAD_FAST 34

1 UNARY_NOT

UNARY_NOT

RETURN_VALUE

and sadly if you try to disassemble yourself with dis.dis() the Python interpreter screams at you because LOAD_FAST gets locals and there clearly aren’t enough locals in () for us to access the 35th. This is an array OOB read.

If you go to the relevant section in the CPython source code, you can see that the instruction LOAD_FAST does

TARGET(LOAD_FAST) {

frame->instr_ptr = next_instr;

next_instr += 1;

INSTRUCTION_STATS(LOAD_FAST);

PyObject *value;

value = GETLOCAL(oparg);

assert(value != NULL);

Py_INCREF(value);

stack_pointer[0] = value;

stack_pointer += 1;

DISPATCH();

}

with GETLOCAL() being defined as

#define GETLOCAL(i) (frame->localsplus[i])

Here, frame is a _PyInterpreterFrame struct. A _PyInterpreterFrame is kind of like the context that bytecode is executed in, storing its locals, stack, instruction pointer, and other properties:

typedef struct _PyInterpreterFrame {

PyObject *f_executable; /* Strong reference (code object or None) */

struct _PyInterpreterFrame *previous;

PyObject *f_funcobj; /* Strong reference. Only valid if not on C stack */

PyObject *f_globals; /* Borrowed reference. Only valid if not on C stack */

PyObject *f_builtins; /* Borrowed reference. Only valid if not on C stack */

PyObject *f_locals; /* Strong reference, may be NULL. Only valid if not on C stack */

PyFrameObject *frame_obj; /* Strong reference, may be NULL. Only valid if not on C stack */

_Py_CODEUNIT *instr_ptr; /* Instruction currently executing (or about to begin) */

int stacktop; /* Offset of TOS from localsplus */

uint16_t return_offset; /* Only relevant during a function call */

char owner;

/* Locals and stack */

PyObject *localsplus[1];

} _PyInterpreterFrame;

localsplus is a special array of pointers that contains both the fast locals2 and the stack used in executing Python bytecode. For performance reasons (presumably), they are consecutive in memory without any padding or any access checks, which lets you do some cool things like access arbitrary values in the stack:

>>> recompile(b"\x19.U\x004\x02$.")

<code object <module> at 0x781349250fa0, file "<string>", line 1>

>>> eval(_)

({'__name__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__package__': '_pyrepl', '__loader__': None, '__spec__': None, '__annotations__': {}, '__builtins__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>, '__file__': '/usr/lib/python3.13/_pyrepl/__main__.py', '__cached__': '/usr/lib/python3.13/_pyrepl/__pycache__/__main__.cpython-313.pyc', 'dis': <module 'dis' from '/usr/lib/python3.13/dis.py'>, 'recompile': <function recompile at 0x781349297420>}, {'__name__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__package__': '_pyrepl', '__loader__': None, '__spec__': None, '__annotations__': {}, '__builtins__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>, '__file__': '/usr/lib/python3.13/_pyrepl/__main__.py', '__cached__': '/usr/lib/python3.13/_pyrepl/__pycache__/__main__.cpython-313.pyc', 'dis': <module 'dis' from '/usr/lib/python3.13/dis.py'>, 'recompile': <function recompile at 0x781349297420>})

This pushes the locals() dictionary onto the stack, then pushes it again but this time by accessing it using LOAD_FAST 0; since there are no fast locals, this accesses the bottom-most element on the stack. You could probably do some cool obfuscation stuff with this.

Anyways, in our case, since our code object comes from compile('()', '<string>', 'eval'), we have zero locals and our stack is also empty when LOAD_FAST 34 is executed. This means that the value we get is just a random value from previous frames’ locals/stack, so the behavior is undefined; in fact in different situations LOAD_FAST 34 will return different results. However, for most Python objects, doing UNARY_NOT twice will give True since they are truthy, so this payload just Happens to Work in most situations. Funnily enough, when I run the challenge file locally with ./chal.py instead of using Docker, LOAD_FAST 34 actually pushes False onto the stack, breaking this payload.

BlahajCTF in retrospect#

I have been part of BlahajCTF’s core team for three years now. If you were at the finale you would have heard from the speech, but at first we had no intention of hosting such a large-scale event. Blahaj “CTF” started out as an… aptitude test(?) for people who were trying to join our CTF team, blahaj. Then, in 2023, we partnered with another student-led CS organisation to produce the very first iteration of BlahajCTF. Back then we had less than 10 challenge authors and maybe about 40 challenges in total. Our infrastructure also was not very stable, and kept crashing.

In 2024, we parted ways with the other organisation and became independent, at the same time expanding and formally setting up our team, bringing in more people to help with challenge creation and publicity. We also managed to secure NTU as a venue, so we could hold a physical finale with about 60 people to end the CTF with a blast. At the same time, we also got a sponsor who was willing to place their trust in us despite how young BlahajCTF was. This was also the year we set our sights on being a beginner oriented CTF, so we had an additional one day training programme over Discord.

This year, we again expanded, inviting more than twice the number of people to finale and having a full 5-day almost 9-to-5 training programme. While I had some concerns about how effective the training would be, it went better than I expected; most training participants managed to learn something new, and some even managed to understand the concept of tcache poisoning. I’ve definitely learnt a lot from organising BlahajCTF this year, both CTF-wise and in general, and I hope our participants did too!

While I’ve had my fair share of hassles and frustrations over the past three years, it’s all worth it seeing people enjoy BlahajCTF. I don’t know if I’ll help out with BlahajCTF again next year due to, ahem, other obligations, but I probably will end up doing so because of FOMO.

Finally, here’s a textwall of appreciation to all the organisers that I’m too scared to put in #challenge-creation: I consider myself truly lucky to have been able to meet and work with so many people passionate about CTFs, and I enjoyed every single moment I spent with you all, online, during training, or at the finale. Whether it be slacking off and drawing during training, rushing to put everything up on the platform the night before quals, or walking around the room during finale so people can see the letter taped to my shirt, I will remember these moments for many years to come. Hopefully it was as enjoyable for you all as it was for me, thank you all for putting in so much work, and may we meet again :)

i think all of them were made by ariana which is very funny. she is a major reason why i started getting into crypto in ctfs ↩︎

you might think that this is the job of

f_localsbut i thinkf_localsis getting deprecated? cpython says that it’s now “a write-through proxy in optimised frames”, presumably tolocalsplus↩︎